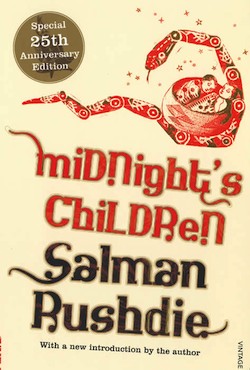

It was Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children that introduced me to the idea of unreliable narration.

Until then, I guess I’d more or less taken my narrators at face value. If they told me it was raining, I believed them. If they told me another character was mean, ugly, stupid, I took their word. Why wouldn’t I? They were the narrator. Wasn’t there some sacred trust between writers and their readers that said that everything the character telling the story said was, de facto, the truth? Unless they openly admitted they were lying, or at least gave me some good, clear reason to doubt them? Surely, anything else would be cheating.

I read — I suppose I should say, studied — Midnight’s Children at university, as part of a course titled “Post-Colonial Literature.” Now that it’s enshrined as a literary masterpiece, now that it’s a Booker of Bookers, it’s probably a book destined to be studied more than it’s read. It was a good course, and it probably wasn’t the tutor’s fault it had been lumbered with such an unfortunate title. While it was going on, we talked far more about Magical Realism; looking back, though, with writers like Rushdie and Márquez forming a good chunk of the syllabus, it could just as easily have been called something like non-Eurocentric Fantasy.

Anyway, as is probably apparent by now, I really liked Midnight’s Children. Amongst its many virtues, it’s a fun, crazy, endless imaginative high-concept fantasy novel — and taken on those terms, I thoroughly enjoyed it. My esteem only grew when I started reading J. Michael Straczynski’s comic book series Rising Stars and noticed how familiar the concept there seemed. Not to accuse Straczynski of plagiarism here — it was more that a handful of similarities clicked into place, something I should have realised all along. Midnight’s Children was a superhero story, one every bit as dense and richly imaginative as anything created by Stan Lee or Alan Moore.

Of all my revelatory moments with Midnight’s Children, though, the highlight was when I found out Rushdie had been lying to me all along. Or, well… not Rushdie, exactly. Rather, his protagonist Saleem, who narrates the entire story. I was delighted to discover, reading Rushdie’s (also excellent) book of essays Imaginary Homelands that he’d seeded his narrative with countless deliberate mistakes, from the tiny to the gigantic. Rushdie’s reasons for doing so are just as varied and interesting, but for now, let’s stick with one: unreliable narration was “…a way of telling the reader to maintain a healthy distrust.”*

*Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands. Essays and Criticism 1981-1991. London: Granta Books, 1991. 22-25.

So here’s a little confession:

My protagonist, narrator of my debut novel Giant Thief, professional wrongdoer and scoundrel Easie Damasco, is none too trustworthy.

Part of me feels I shouldn’t even need to be pointing that out. I mean, the back cover blurb begins “Meet Easie Damasco, rogue, thieving swine and total charmer.” Which of those words could make anyone imagine that here’s a man who’s going to offer them the unvarnished truth? Yet it’s amazed and amused me how willing readers are to trust Damasco. And the truth is, I’m glad. If after reading this you happen to go on to read Giant Thief, I hope you won’t think too much about what I’ve said here. Sure, Damasco’s a thief and a scoundrel, but he’s not a bad person. Well, not exactly. Not all the time. Anyway, it’s his story. Shouldn’t he get to tell it his own way, even if that means the occasional slight exaggeration, distortion or barefaced lie?

Maybe though, just sometimes, you might want to spare a brief thought for who’s telling you that story. In particular, you might want to take Damasco’s assessments of the other characters with a pinch of salt or seven. Moreover, if you do start to have doubts, I hope you’ll gain the odd insight into both Damasco himself and the characters he’s describing and, more often than not, ridiculing.

That, after all, was my personal goal for making Damasco unreliable… that if you read carefully, you’d could find another level of the story, maybe even clues to a wholly different story, buried in the deep cracks of what Damasco does and doesn’t say.

David Tallerman was born and raised in the northeast of England. A long and confused period of education ended with an MA dissertation on the literary history of seventeenth century witchcraft that somehow incorporated references to both Kate Bush and H P Lovecraft. Over the last few years, David has been steadily building a reputation for his genre short fiction and increasingly his writing has tended to push and merge genres, and to incorporate influences from his other great loves, comic books and cinema. David’s home on the net is here and his brilliant blog is here. His debut novel — the Leiberesque Giant Thief — is available now from Angry Robot.